Introduction

Admit it. We’ve all been in a situation where we thought we had an agreement, but it quickly fell apart. A new, hidden agenda appeared, or a new critical risk emerged, and you were back to the drawing board.

What happened?

I’ve collected lessons on alignment over the years, and there are ten consistent things you have to get right, whether you’re on a project board or convincing your family to go somewhere new on holiday. Before jumping into the ten rules, we’ll discuss stakeholders and what alignment means.

What is a stakeholder?

Simply put, a stakeholder is anyone with a legitimate interest in your actions. In a project context, stakeholders might be people that will use what you create. They may pay for it, be impacted by it or be concerned about reputational damage if it all goes wrong. Irrespective of why they have an interest, they are stakeholders.

Not all stakeholders are equal. If you read a book on stakeholder management, you’ll find a discussion on “power vs. interest”, but this is rarely a helpful way to look at stakeholders. Instead, view your stakeholders in terms of what they need to know, what they need to feel or what they need to do for you to succeed. Then, you can view stakeholders by their power level to make things happen. If they have the power to tell, that’s more important to you than the power to influence. There is a third category of stakeholders, who have the power to shape. Another time, we’ll discuss this in more detail, but they are the hidden gems that most PMs don’t realize exist.

What is alignment?

Alignment happens when the decision you need is made by all the people that directly make the decision’s success a reality.

I remember my marketing director making a decision that our legal counsel profoundly disagreed with. Whilst he wanted to force the decision through, the counsel merely needed to say, “You are acting against legal advice”, for the director to realize that we weren’t going live.

Aligned stakeholders matter.

How do I get stakeholders aligned?

Fortunately, there are some simple rules to follow to maximize your chances of alignment. The good news is that they are tried and tested; the bad is that you’ll realize that alignment is a patient person’s game.

Rule 1: Frame the decision properly

Rule 1: Frame the decision properly

I have been on many investment boards where the PM has been vague on what decision they have needed. For example, “We have had an issue with testing, and we’ll need a bit more time to get it right”. How is anyone going to get aligned around that?

Above all else, alignment needs clarity. If everyone has a different definition of “bit more time,” nobody knows the problem, let alone how to solve it. I teach my teams to use the SPINS approach, which is one of the ten stories every PM needs to be able to tell.

The multiple layers of storytelling that get you from the situation to the solution step-by-step are helpful in the SPINS approach. Using it, you can clearly explain how you made the necessary recommendation and why it is correct. The frame is clear, and the logic is clear.

Remember that stakeholders will prefer different languages, emphases and styles. Avoid falling into the trap of trying to cater to every need — find a balance that retains clarity and that people can get behind.

When seeking alignment, frame properly.

Rule 2: Anchor the debate on your terms

Anchoring is a powerful cognitive bias that impacts decision-making more than we’d like to admit. Even being aware of the bias doesn’t make us immune. We tend to over-rely on the first piece of information we come across, and when negotiating or discussing a topic, the debate will centre on that information.

If you’re on the receiving end of a pitch, there are simple approaches to reduce the impact of this bias, such as using the five whys technique. Anything that prevents you from anchoring is good.

However, as the pitcher seeking alignment, anchoring is critical. Without it, your decision will go nowhere, and the conversation will quickly go off-topic. I’m sure we all have been in meetings that started on one subject and finished on another. Anchoring prevents this. You must get your proposal out there as early as possible and centre any debate back on your proposal. If you let the conversation flow away from it, you’ll never get back to what you need.

I see this often in Scrum, where planning events are quickly hijacked by multiple stakeholders’ priorities and nothing of value gets agreed upon without absolute clarity on the frame.

When seeking alignment, anchor the debate quickly on the decision you need.

Rule 3: Build alliances

If you go into a decision-making meeting alone, you will fail almost always. Smart PMs know they must form an alliance before entering the room so that decisions are neither surprising nor controversial.

In social psychology, we call this conformity. It’s a well-researched observation that people rarely go against the prevailing opinion popularised by the Asch experiments in the 1950s. While it’s possible to use conformity for nefarious purposes, it’s essential to understand how to use it positively in a work context.

Status matters. Status can directly equate to seniority, especially in some cultures, but expertise also matters, such as our consumer law counsel mentioned above. Whatever your culture, understand where the power sits and ensure they agree. If you have even a single detractor with credibility, then the best you can hope for is to be sent away to rework your proposal.

Understanding and accepting that building an alliance does not happen overnight is important. Wise PMs have delivery leads that help them run the team, which frees up time to seek and build alliances, but it can take many months. The sooner you start, the sooner you can reap the rewards.

When seeking alignment, build alliances.

Rule 4: Think Small to Act Big

It’s an easy mistake to make. You know every tiny detail of your product, but your stakeholders don’t. What seems obvious and straightforward to you is challenging and risky for your stakeholders. We all fall into the trap of assuming that others will accept our grand plan without any debate, but it rarely happens. That’s why when acting big, it can pay off to think small. Reducing the personal and professional risks you’re asking your stakeholders to take can help to get alignment faster.

When considering how to gain alignment, start small. Unless you’re seeking regulatory approval for an entire design (which may be the case for a power station, for example), then it’s unlikely that you need to align on everything at once. If you can align on something big enough to be meaningful yet small enough to be acceptable, you can prove that you can deliver, and the subsequent alignment can be more extensive. As confidence increases, so do the ideas. The Minimum Viable Product (MVP) concept is precisely what Rule 4 addresses. Get something out there and get feedback.

You may not like having to prove yourself, but in stakeholder terms, it’s often the simplest and fastest route to success. The better you understand what you’re delivering, the easier it is to sequence the necessary decisions so that progress isn’t slowed down.

When seeking alignment, think small.

Rule 5: Use data

“I think”, “normally…”, “The customer wants…”. These are awful ways to get alignment. Why? Typically, when seeking alignment without high-quality data, you’ll fall into one of six traps:

- Generalizations. By taking one experience or opinion and applying it universally, we generalize. One customer thinks the page looks better in yellow, and suddenly we believe they all do.

- Assumptions. We are very good at being creative and filling gaps in our knowledge with assumptions. The problem is that assumptions are almost impossible to back up with facts, and if stakeholders see through them, you won’t be successful.

- Limitations. By jumping to solutions too quickly, we can limit our options unnecessarily. Keeping your mind open can open new possibilities beyond your thinking, particularly with diverse stakeholders. Let the conversations begin.

- Judgements. We can sometimes make judgements based on our own biases. Understanding biases is a rich discipline, but the simple rule of thumb is that if you don’t think your judgement is biased, it probably is.

- Misuse of statistics. The most common abuses of statistics include conflating correlation with causation and not understanding averages. The world would be a better place if we universally understood these errors. Statistics are powerful but use them wisely.

- Stories. Stories are powerful and told well and can trigger strong emotional responses. That emotional response doesn’t make a story true, accurate or even relevant to the agreement you seek. By all means, tell a story to garner support for your decision, but ensure that the story stands up to scrutiny.

These errors can be avoided by carefully using data to tell your story. A good tool you can use to test yours is the fact finder. I’m hoping that v2.0 includes my additions above.

When seeking alignment, use data.

Rule 6: Restrict choices

There are many variations of Buridan’s principle, which refers to a hypothetical situation wherein an ass that is both hungry and thirsty is placed midway between a stack of hay and a pail of water. The ass couldn’t choose between hay and water and died of hunger and thirst.

Choice is good, but too much choice is bad.

Consumer psychologists exploit our inability to choose effectively in almost every area of our lives, from selling branded Aspirin to choosing meal sizes in well-known burger chains. At work, we suffer from the same problems of choice. Avoid long, drawn-out decision-making processes caused by confusion, preference or style. Keep the options simple and distinct.

When seeking alignment, restrict choice.

Rule 7: Use loss and risk aversion

Many organizations are risk-averse, particularly when in the contraction phase of the economic cycle. You can use this to your advantage by showing that the decision you seek alignment on is the least risky choice.

Using anchoring, you can do this by highlighting the risks that other choices would introduce or increase in comparison. If your approach is the default level of risk, you can show that the other options are more risky in comparison.

Loss aversion is powerful and needs to be better understood. Simply put, once we own something, we fear losing it much more than we should. We see this playing out in business in many ways — we hold onto loss-making shares longer than we should, take sunk costs into our decision-making on whether to stop investments and, controversially, use design thinking inappropriately to elaborate our thinking — but then over-value the outcome.

As PMs, we must understand loss aversion and its impact on stakeholders. Are they over-valuing what came before? Do they value the current way of working or functionality more than the data suggests that they should? If so, you must counterbalance the loss aversion with the risk associated with the status quo. Risk > Loss.

When seeking alignment, use risk and loss aversion effectively.

Rule 8: Make your choice the easiest to accept

Whataboutery is a beautiful phenomenon to behold. We’ve all seen it in action. In many meetings, someone will keep asking, “What about?”. Sometimes, it’s a genuine attempt to understand an option, but often is disagreement in disguise. When seeking alignment, however, it can be fatal.

A good PM is a risk management expert who constantly asks what will impede progress and systematically removes those obstacles. Alignment is one of the most significant risks a PM faces, so much attention must be given to ensuring that all the “what abouts” are resolved.

My current record for a pitch is around 250 versions of the PowerPoint deck before I went for approval. I faced engineers, policy gurus and regulatory experts, and all their objections were valid. Nevertheless, after 250 revisions, there were no more objections to the business model I was proposing, and I got my funding from our innovation board. Had I gone to the board too early, as soon as the decision maker asked the technical experts for their opinion, there would have been a torrent of objections. I wouldn’t have had a second chance.

Like it or not, this is the most time-consuming rule to follow. Understand the likely objections and resolve them before you ask for the decision to be taken. Make it easy for your stakeholders by anticipating objections.

Even if there are no objections, go out of your way to make it easy to follow through — remove barriers, steps in the process and minimize what they need to do.

When seeking alignment, be easy to accept.

Rule 9: Repeat, repeat, repeat

At home, we love novelty and spontaneity. It’s what makes our lives fun. However, at work, the opposite is true. We like to know what’s around the corner and that there’s an element of predictability. It’s why we train, it’s why we have processes, and it’s why alignment can be difficult.

Repetition and persistence take some time to be successful. Stakeholders need to hear your idea from multiple sources, sometimes for months, before the “corporate immune system” stops being triggered by your idea. Once those management white cells are no longer triggered, you will more likely succeed.

That’s your cue.

This rule requires patience, persistence and plenty of time. If you’re getting resistance, you can always pull rank or seek a top-down directive, but that’s a short-term game. You might succeed once, but your corporate reputation will be in tatters.

When seeking alignment, repeat, repeat, repeat.

Rule 10: Use different lenses

Psychologists call it the Theory of Mind. It’s the ability to see the world through the eyes of others and understand how they see things. In the context of alignment, by viewing the world through their lens, you can better anticipate stakeholders’ needs, preferences and agendas and find common ground.

Nobody comes to work seeking to block the agenda of others; they merely have their own agenda to follow. If you feel that you’re being blocked, then it’s likely that in meeting your needs, people must compromise theirs. That means that your objective must be to understand their world and priorities. Find common ground, build alliances and seek a win-win.

Remember, as the number of people you need to align increases, the problem becomes exponentially more difficult. If you have four people to align, you need six agreements. If you double that to eight, twenty-eight agreements potentially need to happen.

Seeing the world as others see it is a superpower, particularly in diverse organizations. Many things are not obvious — national cultures, neurodiversity, personal ambitions and even how others feel about you — but you must learn how to use your lenses effectively to succeed.

When seeking alignment, use different lenses.

Summary

Getting alignment is the most challenging part of a PM’s role. Few projects or products fail because of an esoteric planning issue. Most of the time, it’s down to misalignment of expectations or decision paralysis with multiple competing agendas.

Following these ten rules won’t guarantee success, but becoming an expert at aligning agenda is the most important skill you develop. Try the rules out and give feedback on your achievements and challenges.

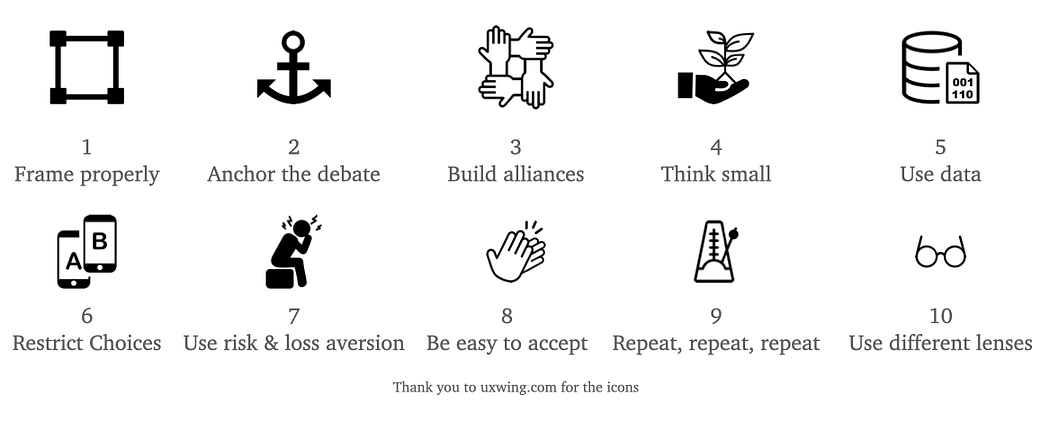

The ten rules:

- Frame properly

- Anchor the debate

- Build alliances

- Think small

- Use data

- Restrict choices

- Use risk & Frame loss aversion

- Be easy to accept

- Repeat, repeat, repeat

- Use different lenses

Notes

For fun, here’s what AI produced for “Write a blog on how to get stakeholder alignment”. Human > AI.

When it comes to achieving success in any project, gaining stakeholder alignment is crucial. Stakeholders are individuals or groups who have a vested interest in the outcome of a particular project. This can include employees, customers, investors, and even regulatory bodies. Each stakeholder has their own set of expectations and requirements that need to be met in order for them to support the project.

The first step in gaining stakeholder alignment is to identify who the stakeholders are. This can be done by conducting a stakeholder analysis, which involves identifying all the individuals or groups who have an interest in the project and understanding their needs and expectations. Once you have identified your stakeholders, you need to prioritize them based on their level of influence and interest in the project.

Once you have identified your stakeholders and prioritized them, the next step is to engage them in the project. This involves communicating with them regularly, providing updates on the project’s progress, and addressing any concerns or issues they may have. It’s important to be transparent and honest in your communications to build trust and credibility with your stakeholders.

Another important aspect of gaining stakeholder alignment is to involve them in the decision-making process. This means soliciting their feedback and input on key decisions and incorporating their ideas and suggestions into the project plan. By involving stakeholders in the decision-making process, you can ensure that their needs and expectations are being met and that they feel valued and invested in the project.

Finally, it’s important to continually monitor and evaluate stakeholder engagement throughout the project. This involves regularly assessing stakeholder satisfaction, addressing any issues or concerns, and making adjustments to the project plan as needed. By continuously engaging with stakeholders and keeping them informed throughout the project, you can ensure that you have their support and alignment, which is essential for achieving success